Content

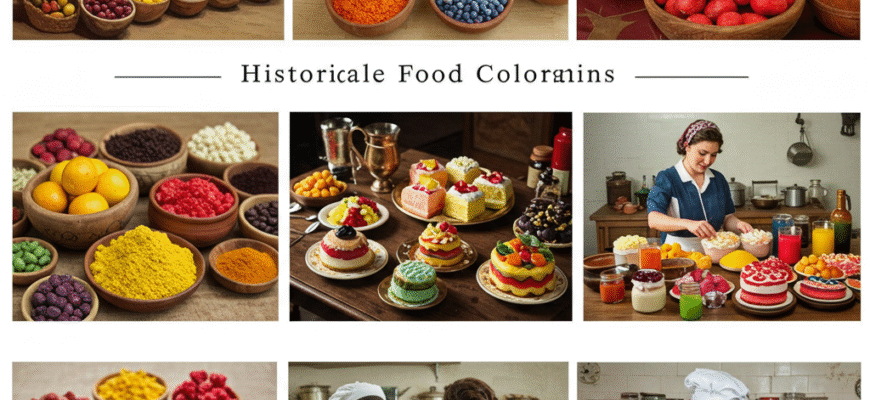

Nature’s Palette: The Ancient World

In the earliest days, adding color to food was entirely dependent on what nature provided. Ancient civilizations skillfully harnessed pigments from plants, minerals, and even insects. Think of the vibrant yellow imparted by saffron, a precious spice derived from crocus flowers, used not just for flavor but for its golden hue in dishes across the Mediterranean and Asia. Turmeric, another root, offered a cheaper but equally brilliant yellow-orange, finding its way into curries and other preparations. Red, a color often associated with ripeness and richness, could be sourced from beet juice or certain berries. For greens, cooks relied on crushed spinach leaves or parsley. Even minerals played a role, although sometimes with hazardous consequences unknown at the time. For instance, cinnabar (mercury sulfide) might have been used for a brilliant red, and lead-based compounds for white or red, practices thankfully long abandoned due to their toxicity. Perhaps one of the most intriguing early colorants was carmine, a vibrant red derived from the cochineal insect. These tiny scale insects, native to South America, feed on prickly pear cacti. Female cochineal insects were harvested, dried, and crushed to produce carminic acid. The Aztecs and Mayans mastered this technique long before European explorers arrived, using the dye for textiles and, likely, food and drink. When the Spanish encountered it, cochineal became a highly valuable commodity, exported back to Europe to color the foods and fabrics of the wealthy.Color in Feasts and Early Trade

During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the use of color in food often signified wealth and status. Lavish banquets featured dishes dyed in bold colors to impress guests. The expanding spice trade introduced new possibilities and reinforced the connection between exotic ingredients and vibrant presentation. A dish colored with expensive saffron wasn’t just yellow; it was a statement of the host’s prosperity. Cookbooks from the period sometimes included recipes specifically mentioning the use of colorants. Almond milk might be colored yellow with saffron, green with parsley juice, or even blue using flowers like borage (though achieving stable blues from natural sources has always been challenging). However, this era also saw the beginnings of food adulteration where color was used deceptively. Cheaper ingredients might be colored to mimic more expensive ones, a practice that foreshadowed later concerns about synthetic dyes.Early uses of color weren’t always benign. Some historical colorants derived from minerals, like lead carbonate (white) or vermilion (red mercury sulfide), were highly toxic. Unaware of the long-term health risks, people sometimes ingested dangerous substances purely for aesthetic appeal. This highlights the importance of safety regulations that developed much later.

The Accidental Revolution: Synthetic Dyes Emerge

For centuries, the world relied solely on natural sources for color. This changed dramatically in the mid-19th century, quite by accident. In 1856, an 18-year-old English chemist named William Henry Perkin was attempting to synthesize quinine, an anti-malaria drug, from coal tar derivatives. His experiment failed to produce quinine, but instead yielded a thick, dark sludge. While cleaning his glassware with alcohol, Perkin noticed the sludge dissolved to create an intense purple solution. He had stumbled upon mauveine, the world’s first synthetic organic dye. Realizing its potential for coloring textiles, Perkin patented his discovery and launched the synthetic dye industry. This breakthrough opened the floodgates. Chemists soon realized that coal tar, an abundant byproduct of coal gas production, was a rich source of organic molecules that could be manipulated to create a vast spectrum of brilliant, stable, and inexpensive colors. It wasn’t long before these new dyes found their way into the food supply. Why rely on expensive, sometimes unstable natural extracts when cheap, vibrant, and consistent synthetic colors were available? Butter could be made a richer yellow, candies could dazzle in every conceivable hue, and drinks could achieve an intensity nature rarely offered. The industrial revolution was transforming food production, and synthetic colors became an integral part of this change, making processed foods more visually appealing and uniform.Growing Pains: Safety Concerns and Early Regulation

The initial excitement surrounding synthetic food colors soon gave way to serious concerns. The industry was largely unregulated, and manufacturers often used dyes initially intended for textiles without rigorous safety testing. Worse still, some colorants contained toxic heavy metals like arsenic, lead, and mercury as impurities or even as part of their chemical structure. Stories emerged of children becoming ill or even dying after eating candies colored with toxic substances. Public outcry grew, fueled by investigative journalists and scientists like Dr. Harvey W. Wiley in the United States. Wiley’s famous “Poison Squad” experiments, where volunteers consumed foods with common additives and preservatives to test their effects, highlighted the potential dangers lurking in the food supply, including unsafe colorants. This pressure led to landmark legislation. In the US, the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 was a major step. It prohibited the adulteration and misbranding of food and drugs, and it specifically addressed color additives. The act initially permitted seven synthetic colors deemed safe based on the knowledge available at the time, establishing the principle that food colorants should be proven safe before use.The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 marked a critical turning point in food safety history. It empowered the Bureau of Chemistry (a precursor to the FDA) to regulate food ingredients, including color additives. This legislation established the foundation for requiring safety testing and certification for substances intentionally added to food, significantly improving consumer protection over time.

The Mid-Century Boom and Emerging Controversies

Following the 1906 Act, further legislation like the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic (FD&C) Act of 1938 refined the regulation of food colors in the US. This act established a system for certifying batches of synthetic colors, ensuring their purity. The list of permitted colors expanded and contracted over the decades as scientific understanding evolved. The mid-20th century saw widespread use of synthetic colors in processed foods, beverages, and pharmaceuticals. However, controversies continued. The Delaney Clause, added to the FD&C Act in 1958 as part of the Food Additives Amendment, stated that any additive found to induce cancer in humans or animals could not be approved. This led to the banning of several colors over the years based on animal testing results, sometimes sparking public debate. One of the most notable controversies involved FD&C Red No. 2 (amaranth). Widely used for decades, concerns about its safety arose in the 1970s, linked to Soviet studies suggesting it might be carcinogenic. Although the data was debated, the US FDA banned Red No. 2 in 1976 due to unresolved safety questions. This event heightened public awareness and skepticism regarding synthetic food additives.The Rise of Natural Alternatives

Growing consumer concerns about synthetic additives, coupled with stricter regulations and labeling requirements (like the E number system in Europe), fueled a demand for “natural” food colors derived from plant, animal, or mineral sources. Food manufacturers began exploring alternatives like:- Beta-carotene: From carrots or algae (yellow/orange)

- Anthocyanins: From berries, grapes, red cabbage (red/purple/blue depending on pH)

- Annatto: From the seeds of the achiote tree (yellow/orange)

- Lycopene: From tomatoes (red)

- Beetroot Red: From beets (red/pink)

- Caramel Color: From heated carbohydrates (brown)

- Spirulina Extract: From blue-green algae (blue)